Sergeant Varlourd Pearson, Distinguished Service Cross.

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Sergeant Varlourd Pearson (ASN: 1449077), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company I, 137th Infantry Regiment, 35th Division, A.E.F., near Baulny, France, 28 September 1918. Though wounded three times by shrapnel and machine-gun bullets, Sergeant Pearson refused to be evacuated and continued to lead the advance of his platoon, remaining in command for several hours till he received a fourth wound which proved fatal.

General Orders: War Department, General Orders 95 (1919). Reported in Military Times

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

Next year will be the 100th anniversary of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive which was fought from 26 September 1918 until the Armistice of 11 November 1918. My grandfather,

James Madison Pearson took part in that battle as did his cousin,

Varlourd Pearson. Varlourd was a member of Company I, 137th Infantry Regiment under the command Colonel Clad Hamilton. The picture I have of Varlourd is as a young boy, perhaps ten or twelve years of age. My grandfather never spoke Varlourd's name. He did tell us of his childhood and the times he his cousins and friends played along the banks of the Tallapoosa River as the Braves of Tallapoosa County.

|

| Varlourd Pearson |

Heroes of the Argonne

The Argonne Forest is a strip of rocky hills and wild woodland along France's north-eastern border with Belgium. It is bordered on the east by the Meuse River. Today, it is two hours by car north of the village of Graffigny-Chemin where my grandmother was born.

The Argonne Forest itself was of no strategic value. It was hilly and wooded and the scattered farming villages were small. But it was the scene of intense fighting between French and German forces in 1915 and 1916 and would be again in 1918, this time with the crucial addition of the American First Army. One can also say with some confidence that the Meuse-Argonne Offensive that took place here lead to the Armistice and the end of World War I.

The morrow of Big Things, chapter 7 in the book

Heroes of the Argonne: An Authentic History of the Thirty-fifth Division by Charles B. Hoyt, 1919, retells the story of the first day of battle.

|

| Map of Meuse-Argonne Offensive battle order of 1st Army and 35th Division |

The First Day

Nine divisions of American troops under the command of General Black Jack Pershing, faced four German divisions under the command of General von Marwitz.This is not to say the odds favoring the Americans were overwhelming. On the contrary, the Germans were well-entrenched with a system of caves and trenches. There were bunkers and pill boxes and the throughout the Germans had deadly machine guns which could kill by the dozens and hundreds in a matter of minutes.

The place was Vauquois Hill. It was by 1918, a grey cratered landscape shelled beyond recognition. The village of Vauquois, which had been at the base of the hill was gone.

|

| Vauquois Hill, 1916 |

Vauquois Hill

The hill of Vauquois was strategic for both sides, because who held the hill overlooked the land east of the Argonne Forest and the supply routes leading to it. It was the Germans first line of defense in what had become a defensive war. Behind this, the Germans established the Hindenburg Line, behind this the Kriemhilde Stellung, and behind that the unfinished Freya Stellung.

|

| Operations of 35th Division Meuse-Argonne, credit Charles Hoyt, Lyons |

The Night of Stars

Sergeant Varourd Pearson was a member of Company I, 137th Infantry Regiment (Kansas National Guard formed in Manhattan), under the command of Colonel Clad Hamilton. This unit was part of the 35th Division (Kansas and Missouri National Guard, which included Captain Harry Truman, Battery D, 129th Field Artillery), under the command of General Peter Traub, part of the First Corps under the command of General Hunter Liggett.

The evening of the 25th of September was a night of stars, unusually dark and unusually quiet except for the occasional whizz of a German sniper bullet. The peace was interrupted at 2:30 am on the morning of the 26th by an artillery barrage, but the soldiers still had a few hours before the attack.

Along with his helmet, canteen, rifle and bayonet, an infantry soldier carried 250 rounds of ammunition, and, on his back, a raincoat and mess kit, plus three days rations, consisting of two cans of “bully beef” and three tins of “biskwee” or hard tack. On his belt hung incendiary grenades, explosive grenades, and rifle grenades to attack machine gun emplacements and hardened dugouts.

Dawn Approaches on the 26th of September

As dawn approached, the night of stars gave way to a dismal scene of fog and smoke. The deafening artillery barrage came from both sides now. The earth which once trembled, now heaved and rocked as heavier artillery commenced firing - 75mm guns, 77’s, 110’s, and 155's; and tens of thousands of screaming shells, naked to the eye but heard by every frightened soul, cross-crossed the sky.

At 5:30 am the advance began. The honor of leading the attack went to the 69th Brigade, with the 137th and 138th Regiments abreast. Brigades and regiments would advance by battalion in staggered columns with 500 meters separating the battalions. The 137th regiment was followed by the 139th, tasked with cleaning out the trenches of remaining Germans.

|

| Operations of 35th Division Meuse-Argonne, credit Charles Hoyt, Lyons |

Sergeant Varlourd and the 137th's advanced with rifle and bayonet against machine gun nests dug into the side of Vauquois Hill. A German photo taken in 1915 of the Argonne Forest gives us an idea of the terrain, a snaking mass of barbed wire and the gnarled, splintered trunks of trees. The terrain would have been difficult in the best of conditions, but in the smoke and fog, against machine gun fire and artillery, it was hell on earth.

|

| Argonne Forest, 1915, German archives |

By 7:40 am, the American artillery barrage ceased. The 137th was on its own. Eventually, Sergeant Pearson and his fellows made their way through the woods to a point south of Cheppy on the way to Charpentry.

|

| Cheppy, France, World War I |

The 27th of September

At the first light the soldiers of the 137th pressed on. To their left, the 28th Division struggled in the woods of the Argonne Forest. This left the men of the 137th open to flanking fire, forcing Sergeant Pearson and the 137th west towards Varennes. A mile south of Varennes, on the Neuvilly-Fleville road, Sergeant Pearson and the 137th could now see the tall steeple of the church at Varennes. Their advance was stopped by German artillery fire, and Sergeant Pearson took shelter with his company in abandoned German gun emplacements. As the bombardment ended and now joined by French tanks, they advanced taking the village of Varennes.

When the day ended, the Americans had also taken Montblainville, Charpentry, and Baulny. Sergeant Pearson could now relax and break out a tin of Bisk-wee and a can of Bully Beef and take a drink of water.

The 137th awaited the still advancing Americans units on the right, and the regiment was now a jumbled mixture of men from different units.The number of casualties at this point is unknown, but when the offensive woul end, the 137th would record casualties of nearly 1,300 men of the 2,800 soldiers who fought.

The day of the 28th of September

An advance was ordered for 5:30 the next morning - the objective, Exermont.

Sergeant Pearson awoke on the morning of the 28th. It was cold and cloudy. The air filled with a fine rain. Perhaps he put on his raincoat, perhaps not for that would have made movement hard. It is more likely that he continued on cold and wet. At 6:30 am, the Germans counter attacked and were driven back. The 137th advanced a mile and a half that day, and their front lines would form its own salient into the German lines, and the heaviest loss of lives would be recorded.

The

Kansas Guard Museum continues the story.

[The 137th Regiment] encountered severe machine-gun and shell fire, particularly from the Montrebeau Woods, ... a short distance north of Baulny. By this time the advance had turned slightly to the west, more or less following the bank of the Aire River. By night the men had secured a hold on the edge of the woods, but they were not in possession of it. A mile and a half had been attained by the end of that day’s operations.

Sergeant Pearson would not live to see the night. The citation reads::

Though wounded three times by shrapnel and machine-gun bullets,

Sergeant Pearson refused to be evacuated and continued to lead the

advance of his platoon, remaining in command for several hours till he

received a fourth wound which proved fatal.

|

| Exermont, WWI |

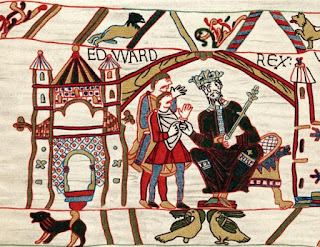

Our own clan chose Wilmslow, Mobberley and the surrounding hamlets in Cheshire County. The city of Chester was the terminus of the Norman conquest, and some historians think that the Pearson name came to England via the Norman Conquest of 1066 A.D.